"Happiness in marriage is entirely a matter of chance.”

—Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice

“Marriage,” writes Professor Martha Bailey, LLM'88 (MSc'14), “is the central theme and conclusion of Jane Austen’s novels.” From her first published book, Sense and Sensibility, to her last, Persuasion, Austen’s plots centred on the intricacies of marriage, from engagements and financial settlements to clandestine weddings, adultery and illegitimate children.

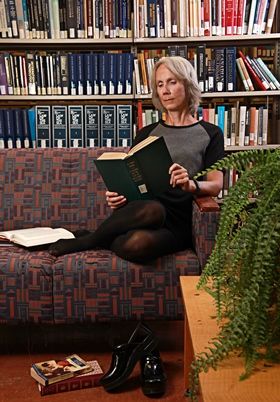

Bailey has long been a Jane Austen fan. “In law school, I re-read all her novels when I was supposed to be studying for exams!” These days, she teaches contracts and modern/Canadian family law at Queen’s Law. When she decided to take a closer look into the laws of marriage in Regency England, she found some illuminating things that helped her gain a deeper understanding of Jane Austen’s work – and her world. Bailey recently presented her findings at an Austen conference in Louisville, Ky., last month, “Living in Jane Austen’s world.”

Marriage, for women living in that world, was a career choice, and one that had to be made wisely. Proper young women could be governesses or they could be wives. A very few could become novelists, but even Austen herself would never live off her earnings as a writer. Men from impecunious families had a few more career choices – such as the church and the army – than did women. In Austen’s world, marrying for money alone was not good, but marrying when neither partner had a fortune was imprudent. Marrying solely for love? Unheard of.

In her paper, “The Marriage Law of Jane Austen’s World,” Bailey explores the business of marriage and explains the legal precedents to some of Austen’s storylines. For instance, in Pride and Prejudice, clandestine marriage to a young bride is a major plot point, first in the story of George Wickham’s planned elopement with Georgiana Darcy (then aged 15), and then in Wickham’s marriage to Lydia Bennet, aged 16. And while their ages were a factor in both families’ objections to the unions, each woman was, in fact, over the age of consent by law. However, as Bailey writes, “The problem with such marriages was that they took place over the often well-founded objections of the family. Legislators sought to prevent all such problematic marriages by imposing rules against private ceremonies.”

Lord Hardwicke’s Act (1753) required public church announcements (called banns) of intended marriages, to allow, in part, for objections to be raised. The act allowed for special licences without the reading of the banns, but these required parental consent in the case of minors. When Wickham and Lydia elope, much of the book’s tension comes from the couple’s unknown whereabouts. They could have crossed the border to Gretna Green in Scotland (the act only applied to marriages in England). Or they could have set up house in London, and had their banns read without the knowledge of Mr. and Mrs. Bennet. In the end, Lydia Bennet becomes Mrs. Wickham after a financial agreement is brokered (by Mr. Darcy). The cost of a legitimate marriage, even to a despicable groom, was much less than the cost of a young woman’s reputation (and to her sisters’ future marriage prospects.)

Bailey also challenges a few misconceptions about British law that both the modern reader may make – and that Austen herself may have made. A favourite book of Bailey’s, plucked from the shelves of the Lederman Law Library, is the 1836 tome The Laws of Adulterine Bastardy. This volume, among others, helped her to untangle the nuances of the plot of Sense and Sensibility. In this work, a girl, Eliza Williams, is said to be the result of “a guilty connection.” Readers of Sense and Sensibility have long understood this to mean that Eliza was an illegitimate child. And while Georgian society took a wholly disapproving view of children born out of wedlock, the laws of the time (without the benefits of modern science to determine paternity) needed much more evidence to rule that a child was illegitimate. Jane Austen herself might have been surprised at the legal presumption of legitimacy of her fictional Miss Williams.

By Andrea Gunn