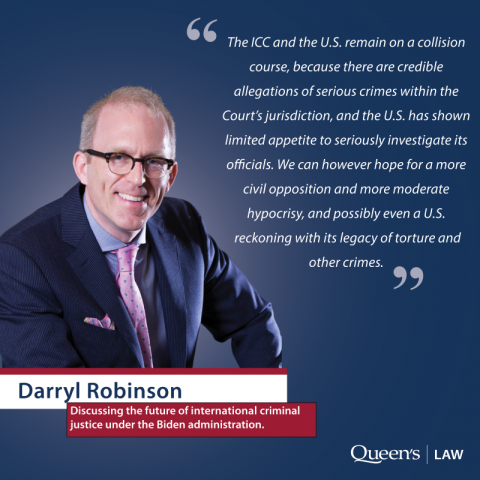

With the Biden inauguration dominating international news, six Queen’s Law experts are stating their predictions for how the new government will have an impact on Canada and across the globe. In today’s feature of the six-part series, Professor Darryl Robinson examines international criminal justice.

Turning international justice right side up

In 2020, then-President Donald Trump adopted an executive order that, in normal times, would have generated sustained international condemnation and pressure until it was repealed.

The executive order authorized personal sanctions against lawyers at the International Criminal Court (ICC) and others who support the ICC. Such sanctions have previously only been applied against terrorist organizations or regimes that commit mass crimes.

The sanctions were imposed because the ICC is looking at credible allegations of torture by CIA officials in sites in Afghanistan. Afghanistan is an ICC member and thus falls within the Court’s territorial jurisdiction. Thus, these officials are doing their jobs, investigating war crimes within their legal jurisdiction.

So far, the U.S. has imposed sanctions on Chief Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda (Gambia) and Phakiso Mochochoko (Lesotho), the director of the situation analysis division, as well as their families. The sanctions freeze their assets and ban them from the U.S. The asset freeze has complicated their ability to travel on missions, since most transactions are in U.S. dollars.

The sanctions attracted international condemnation from ICC member states, who argued that they “treat human rights investigators like terrorists” and that “sanctions are a tool to be used against those responsible for the most serious crimes, not against those seeking justice.”

The U.S. has long been a big supporter of “justice for others;” it led the way in creating international tribunals for crimes by others. The ICC is based on firmly established principles of jurisdiction that the U.S. itself helped create. But the idea of foreigners even-handedly applying those same principles to Americans is, for many in the U.S., self-evidently outrageous.

These sanctions punish prosecutors and judges for appropriately applying rules. This upside-down approach is very much in line with the Trump era: lies are truth, treason is patriotism, impartiality is corruption, fair is rigged. And now, seeking justice is criminal.

Under the Biden Administration, this order will surely be rescinded. But this does not mean that things will be rosy. The double standard in American thought runs across party lines. The ICC and the U.S. remain on a collision course, because there are credible allegations of serious crimes within the Court’s jurisdiction, and the U.S. has shown limited appetite to seriously investigate its officials. We can however hope for a more civil opposition and more moderate hypocrisy, and possibly even a U.S. reckoning with its legacy of torture and other crimes.

Professor Darryl Robinson specializes in international criminal law. As the first adviser to the Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, he helped shape its first policies and strategies from 2004 to 2006. His new book, Justice in Extreme Cases: Criminal Law Theory Meets International Criminal Law, was published by Cambridge University Press in December 2020.